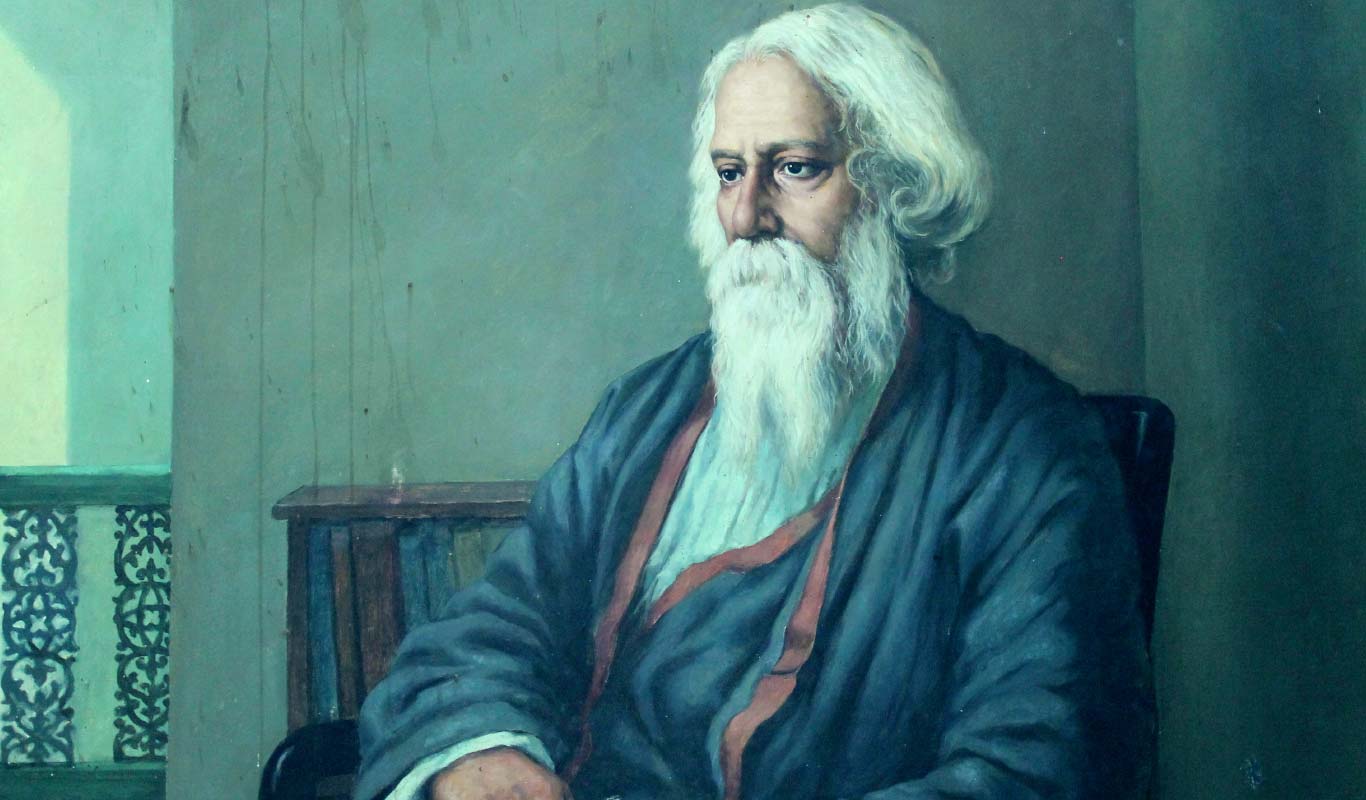

Jacques Derrida (1930-9 October, 2004) is a philosopher everybody has heard of, but few non-specialists can manage to read; a clear case of ‘many are called but few are chosen’. Opinions of him range from those who say he is one of the greatest philosophers of the twentieth century to those who say he was a charlatan. In the mid-1970s he had a debate of unusual acrimony with the distinguished American philosopher of language, John Searle. In 1992 he was almost refused an honorary degree at Cambridge because of the opposition of several philosophers, some of them eminent. So, a controversial figure.

The question of why Derrida’s texts are so difficult is interesting in itself. One reason is the unfamiliarity of his concepts. Another is his concern that statements asserting knowledge always assume other knowledge. As Hilary Lawson says in his excellent 1985 book Reflexivity: The Post-Modern Predicament, “our ‘certainties’ are expressed through texts, through language, through sign systems, which are no longer seen to be neutral. It appears, therefore, in principle there can be no arena of certainty.” Derrida wants to avoid making statements which depend either on fixed linguistic meanings or on assumptions made elsewhere.

So what is Derrida trying to say to us?

The Problem With Logocentrism

I want to try to answer this question by concentrating on the first part of his early book Of Grammatology (1967), which I believe is the Rosetta Stone that gives us the key to all his writings.

He takes a lead from the Swiss linguist Ferdinand Saussure (1857-1913), who maintained that words derive their meaning from other words, and that meanings work by differences not similarity. For example, we notice that a triangle differs from a square. Neither are related in our minds to some ultimate standard shape; instead we know them by their differences from each other. Similarily, we can’t trace meanings of words back to any gold standard. If we want to know the meaning of a word we look in the dictionary, and this defines it in terms of other words. If we want to know what they mean, we have to look them up too, and so on ad infinitum, or at least until we have arrived at words we think we already understand. But there is no natural connection between the word (Saussure called this the signifier, eg the written or spoken word ‘dog’), and the idea or concept the word stands for (the signified; the general concept ‘dog’). Signs are composed of the relation between the signifiers and the signified. The connection between the signifiers and the signified is a practice or norm which has been built up over time, which continues to evolve, and is of course different in different languages. To learn the links, that is, to learn the meaning of the words, we have to learn the practice.

A trace of Jacques Derrida low quality scan of a printed card sent to Philosophy Now by Jacques Derrida himself in about 1993.

Writing which argues a case, such as philosophical writing, often attempts to reduce meanings to set definitions; those definitions in turn depend on the signifier and its relationship to the signified. This is motivated by a desire for a focal point for understanding. Derrida calls this sort of desire logocentrism, which means aiming to try to get to the logos, the ultimate definition, which might be called true knowledge by some.

Logocentrism initially implies phonocentrism. Originally, Western philosophy relied on speech rather than writing. Socrates never wrote a book; instead he argued with people in the marketplace. Later philosophers, including Aristotle, also championed speech over writing. Speech is somehow considered closer to the thinking of the speaker. Derrida argues against this prioritising at some length in Of Grammatology. I shall not concentrate on this argument but on Derrida’s proposals for the interpretation of texts.

Philosophy works through language, and constantly makes the logocentric assumption that stable meanings of concepts – set definitions – are available to us. But because a signifier (word) and the signified (its conceptual meaning) have more independence than we would perhaps like to think, there is not always a single, fixed meaning, so texts are capable of more than one interpretation.

Take the word ‘justice’. The word signifies an abstract concept. Our concept of justice is moreover associated with the concrete institutions of justice – the courts, the police. The complainant wants justice (in the abstract), and looks to the courts for it, and considers the abstract concept and what the courts deal in as the same. But are they? Meaning evolves all the time, and the concept of justice changes: it would have had a different meaning in the minds of most people before there were any courts. On the other hand, one concept of justice – these days the institutional concept – is likely to dominate.

This flexibility also means that texts are capable of more than one interpretation. Peter Benson gave a good example of this in this very magazine: “the medieval Christian approach to the Bible declared there to be four ways to read each passage: literal, anagogic, typological and tropological. These interpretative traditions have been challenged by fundamentalists, who seek to pin an immediately-known fixed meaning to every word… Fundamentalism is therefore one manifestation of the metaphysics of presence. From Derrida’s perspective, it involves a misunderstanding of the nature of language” (Issue 100, 2014).

The Presence of Derrida

In Of Grammatology Derrida introduces the important phrase ‘the metaphysics of presence’. What does he mean by this?

Logocentrism leads immediately to the favouring of present certainties. This is something that’s done automatically by Western philosophers, particularly metaphysicians. Indeed, we all seek certainty: we want to know if and what God is, what the good is, what our Being is, why we are here… Moreover, we rely on language to tell us the answers. The Western philosophical tradition as a whole insists on chasing objective truth, demanding certainty in the present; and to achieve this it relies utterly on the connection between the signifier and the signified, between words and their meaning in the text – words which have no gold standard for that meaning but are defined from other words. This is already a problem for the meaning of metaphysical texts, which therefore do not have fixed meanings. Derrida’s thesis is further that metaphysics seeks not only to impose an interpretation in the present, but also seeks transcendental signifieds – concepts which overarch past and future, near and far, similar and dissimilar. Such metaphysical concepts are incoherent, a prioritising of presence and similarity at the expense of change and difference. We would like, here and now, to define God, the good, our Being, and many other impossible-to-define things, all with certainty, simply, with as few words as possible. But we can’t.

So it is words that are the problem in metaphysics, as they need continual reinterpretation. Perhaps philosophers are aware of this. In ‘Philosophy as a Kind of Writing: An Essay on Derrida’ in New Literary History, Vol. 10, No. 1 (Autumn, 1978), the American pragmatist Richard Rorty points out that scientists use few words to describe conclusions from their experiments. It is philosophers, and investigators of things that are impossible to know, who need to write and rewrite, and to re-interpret and re-visit problems. And especially, it is metaphysicians. Rorty says, “it is characteristic of the Kantian tradition that, no matter how much writing it does, it does not think that philosophy should be ‘written’ any more than science should be. Writing is an unfortunate necessity; what is really wanted is to show, to demonstrate, to point out, to exhibit, to make one’s interlocutor stand at gaze before the world… [whereas] In a mature science, the words in which the investigator ‘writes up’ his results should be as few and as transparent as possible.” (p.141).

One might be inclined to say “So what?” Everybody knows that scientists write up experiments and philosophers write essays, and that writings can be interpreted in various ways. But it goes further than that. Derrida’s critique of metaphysics is not limited to the shaky relationship between signifier and signified. Derrida is famous as the inventor of deconstruction.

Interpreting Deconstruction

More meaning is available from a text than any immediate intuitive interpretation of the words and concepts. As well as the alternative interpretations beloved of all critics and commentators, there are hidden meanings in texts not necessarily intended by the author. Deconstruction is an attempt to prise out these hidden meanings. As Derrida puts it in Of Grammatology, deconstruction aims to “designate the crevice through which the yet unnameable glimmer beyond the closure can be glimpsed” (p.14 in G.C. Spivak’s translation). It is important to note that deconstruction, at least as conceived by Derrida himself, is not a method – it has no clear modus operandi. Instead, it is a way of reading texts by opening them to question, all the time asking: is that the only essence or meaning of a concept?

To understand this better, we need more concepts. Derrida defines (well, given his reluctance to commit himself, sort of defines) what these are in Of Grammatology, Part 1. There he claims that metaphors and metonyms are always present in writing, whether intended or not. The meaning of words, he says, is often only understandable by their metaphoric implication.

Since words are only defined by their difference from other words there are also binary hierarchies, pairs of words which are defined by their opposites such as left and right, male and female, presence and absence. Take justice again. Whenever the word is used it implies something about injustice. The path or trace to its definition is accompanied by its opposite in a binary hierarchy. If one says or writes “man”, one means “not woman”. So a word contains a trace of what it does not mean, and the trace is there but not there, the track of something absent. There is a Freudian element here. All signifiers have a history, they are changed by history, but understanding has to take place in a present.

For clarity, I have taken a liberty in being more definite than Derrida, who refuses to define a trace as a concept. It is easier to see why if we regard a language as a flexible system. Words, defined by their differences from other words, not by some gold standard, do not maintain meaning; rather they change in meaning over time and in different contexts. The trace represents that change. It is not even itself a static concept.

Derrida sees binaries as a problem for metaphysics because metaphysicians tend to be biased towards the dominant word in the binary hierarchy. It is unjustified and misleading, but pervasive. As he writes: “All metaphysicians, from Plato to Rousseau, Descartes to Husserl, have proceeded [by] conceiving good to be before evil, the positive before the negative, the pure before the impure, the simple before the complex, the essential before the accidental, the imitated before the imitation, etc. And this is not just one metaphysical gesture among others, it is the metaphysical exigency, that which has been the most constant, most profound and most potent” (Limited Inc, 1988, p.236.). Writers about feminism have, not surprisingly, taken up this notion of dominance bias.

The definition of words by their difference from other words goes further. It can also be deferred, so that no meaning of any word is ever fully present. The deferring of meaning can take place in time or context, or simply because a meaning is subjugated to a related or opposite meaning.

The process of differing and deferring is combined into one word by Derrida – differance. This word indicates that words (signifiers), as well as being defined by other words (signifiers) from which they differ, also have their meaning deferred as the meaning constantly changes. This differing and deferring process goes on continually when using a language or understanding texts. Texts may have different meanings to the perceiver on re-reading. Words change as contexts change too. This flexibility in interpretability is easy to see with government legislation and legal rulings, which require expert interpretation. And my conception of this article will be different from your conception, and in any future rereading, our conceptions may also differ, either more or less than they do now. If we were reporting the reading from an instrument such as a galvanometer or a weighing machine dial, our conceptions would not differ nearly as much. But in situations where it is hard to put our finger on what is meant – as in philosophy articles – our conceptions may vary radically, and some discussion between us (using yet more words) might, or might not, enlighten us both.

Hilary Lawson illustrates the implication of the concepts of the metaphysics of presence, trace, and differance well in his example of a statement of the form ‘the chair is black’. He writes: “we are not able to prove the truth of the statement… by going to look at the chair, for there is no present experience which provides the data against which we can check the statement…” rather, “there is no single meaning of the sentence ‘the chair is black’, and there is no single meaning to our experience at any point. The meaning of the sentence takes place in the play that is the web of language, and experience is not an independent thing which stands outside of that play” (Reflexivity, p.100). The sentence is therefore devoid of the means of physical verification, and we will each conceive the meaning of the statement differently.

These are the rudiments of deconstruction.

(No Definite) Conclusions

There is, of course, a great deal more to Of Grammatology than I have indicated here. As well as arguing against the prioritisation of speech, Derrida attempts to work out whether grammatology, a science of writing, is even possible. He reaches no definite conclusion. His difficulty seems to be that science seeks present solutions successfully, for the most part, unlike metaphysics. He is doubtful whether such solutions would be available for texts. He also has much to say on other philosophers (particularly Nietzsche, Husserl and Heidegger) and linguists (particularly Saussure, Peirce, and Jacobson). He criticises the two dominant philosophical movements of his day, phenomenology and structuralism, as both indulging in the metaphysics of presence. And that’s only Part 1. The second part of the book is given over to putting deconstruction into practice, particularly for the writings of Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Claude Levi-Strauss.

Derrida spent much of the rest of his career, particularly the early part, deconstructing the work of philosophers and other writers, often showing that their meaning was unclear, and that their texts often said more than they intended. There is much to read; Derrida was one of the most prolific of writers.

The intention of this article has been to give a brief introduction to the way Derrida’s thinking works. He would have no doubt hated my attempt to provide such a closed summary of meaning and reference. But to quote him out of context, I have aimed only to “designate the crevice through which the yet unnameable glimmer beyond the closure can be glimpsed.”

Author :

Mike Sutton

Mike Sutton lives in Birmingham and writes about philosophy, sociology, science and technology.