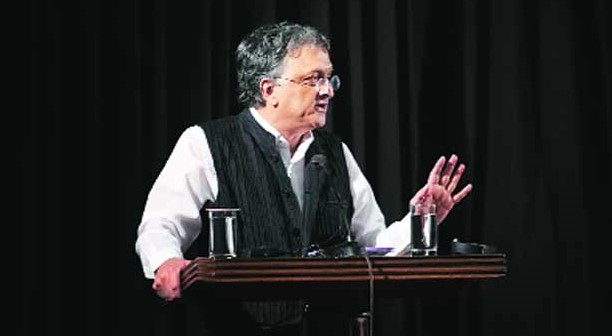

This interview with Edward Said took place on 8 September 2000 in New York City. Three years later, on 25 September 2003, Edward Said died of a rare form of leukemia that he had struggled with since 1991. On 28 September 2000, just weeks after our interview, in a deliberate effort to head off the declaration of statehood by the Palestinians, Ariel Sharon, not yet Israeli prime minister, led an escort of Israeli Defense Forces to Haram-esh-Sharif, or Temple Mount, regarded as the third most holy site in Islam. The al-Aksa intifada that resulted from this deliberate provocation is still going on, at the cost of more than 3000 Palestinian lives and 500 Israeli lives, and untold property damage over three years. Even before these events, Said is prescient in anticipating that the road to Palestinian statehood would once again be blocked. At the same time he makes a compelling argument for why contemporary attempts at statehood were doomed.

Edward W Said was one of the preeminent literary critics of the 20th century, a public intellectual of the highest caliber, known throughout the world for his 1978 book, Orientalism, which inspired the founding of postcolonial studies and radically altered the trajectory of several established disciplines. He was one of the firstö certainly the most trenchantöamong intellectuals to expose the connections between liberalism, the Enlightenment, and imperialism, an exposure made more potent by his personal history of displacement from Palestine in 1948

Orientalism resonated deeply with geographers who in the 1970s and early 1980s were deeply immersed in questions of imperialism, racism, uneven development, and social reproduction, among others, and who were just beginning to link cultural critiques of capitalist expansionism to political economy. But the writings of Edward Said suggest a rich geographical imagination at the roots. Of all his work, it may have been Culture and Imperialism, published in 1993, that provided the greatest stimulation for geographers. In that book he not only engages with geographical writing but uses the litany of colonial and especially anticolonial writings to propose the necessity of `rival geographies’ in order to reveal “what is essential about the world in the past century”. Here Said conjures up a profundity to historical and political geography that remains exemplary. Cultural critique remained circumscribed, Said argued, unless it also engaged the geographical and political critiques of imperialism, and vice versa. Unlike many literary critics for whom the language of geography is before anything else metaphorical, Said’s geography was deeply material, interlaced with politics, emotion, and history. The power and passion of these connections were undoubtedly fueled by his biography: a lifetime spent as an exile, however privileged, from a dispossessed Palestine. The autobiography of his early life, Out of Place (1999), is not only riveting reading but makes explicit the importance of childhood geographies in the making of a radical intellectual. Not at all in his spare time, he also wrote extensively about music and played piano with passion and the skill of a concert pianist. Beyond his intellectual contributions, Said is undoubtedly best known, indeed renowned, for his powerful, critical, and determined support for Palestinian independence. An independent member of the Palestinian National Council from 1977 to 1991, he was outspoken about the dispossession of Palestine after 1948, carried out with US and British support, and the oppression of Palestinians ever since. Never one to understate the tragedy of the Holocaust, he nonetheless insisted that the solution to that horrific episode, and the salving of the world’s guilt for letting it happen, should not have been carried out at the expense of Palestinian sovereignty, livelihoods, and lives. He was adamant that the question of Palestine focused not only on the conditions of repossession of land for the Arab population of Israel but also on the right of return for exiled Palestinians. Yet he broke with Yasser Arafat after the Oslo peace accords, which he viewed as a massive sellout to Israeli belligerence, a `Palestinian Versailles’, as he called it, referring to the draconian conditions foisted on the losers of World War 1. There was no option, Said believed, but for Israel and Palestine to coexist in the same territory, albeit perhaps with separate states, and for this geographical compromise he took criticism from both sides. Vilified worldwide but especially in his adopted New York City by Right-wing Zionists and supporters of Israeli anti-Palestinian violence, his university office was at various points protected by campus police. True to form, in a disgraceful obituary, the New York Times painted Said as a terrorist or at least a terrorist sympathizer, “the professor of terror”, as one extremist magazine wrote. At the same time, he was ostracized by many in the Palestinian Authority for being too willing to make compromises with Israeli claims.

Edward W Said was an extraordinary political and intellectual presence for all of us. His critical intelligence, expressed so many times in his courageous and principled stands for the self-determination of oppressed people all around the world, will be widely missed. In Culture and Imperialism (1993), for instance, he took direct aim at the `Bismarckian despotism’ of Saddam Hussein, yet in later days, quite consistently, he lamented the war against Iraq as a dramatic tragedy of a failing US imperialism. He was nothing if not an equal-opportunity indictor of oppression, an intellectual in the profoundest sense, who more than once infuriated his political allies by dishing out to them the same kind of stringent critique that was usually aimed at the perpetrators of oppression. Whether because of this or as a result, and whether laudable or questionable, Said retained an equally profound sense of independence from organized political parties.

Edward Said was a charming and gracious man who, had he not lived in a country that systematically ignores its intellectuals, especially those on the Left, would have had an even greater effect on the world; his obituaries in Europe were far more numerous and laudatory than those in the controlled media of the United States. Whether in an interview or in casual conversation walking down the street, he spoke in complete paragraphs with extraordinary erudition. Astute and nimble on his feet, and a man of extraordinary intellectual depth and breadth, Said’s insistent engagement with geography in the broadest sense will be a source of continuing fascination for years to come. “[G]eography”, he says in the interview, with a sensibility rare for one who lived in New York since the 1960s, “is the only way that I can coherently express my history”. The making of geographies, for Edward Said, also represented a means by which his politics took form, while political contests, he understood, were integral to making these same geographies.

Neil Smith You have been very explicit, I think, that geography is not the solution to conflict between Palestine and Israel. Why not?

Edward Said As things now stand, there’s every likelihood that some kind of Palestinian state entity will be recognized, but it will be recognized as part of what I would call a kind of permanent interim settlement. Just as Israel was recognized by many countries in 1948 as a state without any declared boundaries, this one will be too. It won’t have any declared boundaries and that will be something for negotiation for a long time to come. The realities on the ground, which are completely occluded in the media, are that, no matter what kind of state comes into being (whether one that he [Yasser Arafat] declares against the Israeli will or one that comes into existence because of negotiations between him and the Israelis and above all the Americans) it will be a state totally dependent on Israel economically. That’s the first thing to note. Second, it will be at the mercy of Israeli security so that it will not have the power to let people in and out; that will still be in Israeli hands as it is today. Third, it will not have contiguous territory, a very important point. That is to say, if it comes into being now there will be several cantons, all of which will have to be connected via Israeli territory so Israel could cut off one canton from another.

There lies the nub of the whole conflict between us. It is the question of dispossession. It’s the question of return. And the question of acknowledgment for what has been happening. The last point I want to make about the current negotiations, is again excluded from the media analysis, the number one Israeli demand which they put to Arafat and want him to sign, is the end of the conflict. I mean Jerusalem is important and so on and so forth, but refugees are more important because they are a bigger and longer run problem.

NS Like Bophuthatswana within South Africa?

ES Exactly, it’s the same model. Or reservations in a Western state and so forth. If it comes into existence under the aegis of the Israelis and the Americans because of negotiations, Gaza and the West Bank will be totally separated. They are 25 miles apart and the land bridge will be controlled by Israel. So, that’s the third thing. Fourth, it will be the only state in the world that I know of that will have no sovereigntyö properly speaking. It will have autonomy, it will have a municipal government, it will be responsible for the well being of its citizens, but it won’t be able to do what sovereign states normally do, namely control the borders and the things I mentioned. And last, it will not be a state where Palestinians can easily be repatriated. And, contrary to what the press has been saying, the main issue between the Palestinians and the Israelis (regardless of what Arafat and Barak agree on) is not the question of Jerusalem but the question of the refugees. That is to say, there are now 4 million Palestinian refugees in the world who are stateless, many of them in Lebanon and Syria and Jordan (not all of them in Jordan are stateless, but they are refugees nonetheless and they have a lesser status than Jordanian citizens), Egypt, Libya, other parts of the Arab world, the Gulf, Europe, North America, Australia, etc. And there is no provision, in the discussions so far, for anything more than about 100 000 of them. So the Israelis are willing to accept 100 000 refugees as what in Arabic is called lemshan, which means family reunification. In other words, if you’re a patriarch and 80 years old and you have grandchildren and so on in Haifa, then you’ll be able to come back if you apply. All of this is of course at Israel’s discretion. The rest will have to be negotiated between Israel and the PLO: how many of them will be allowed back to the West Bank and Gaza (the Palestinian State), but not their homes in what is former Palestine.

I think that’s the main problem. There lies the nub of the whole conflict between us. It is the question of dispossession. It’s the question of return. And the question of acknowledgment for what has been happening. The last point I want to make about the current negotiations, is again excluded from the media analysis, the number one Israeli demand which they put to Arafat and want him to sign, is the end of the conflict. I mean Jerusalem is important and so on and so forth, but refugees are more important because they are a bigger and longer run problem. And ending the conflict is the most important question of all, because if Arafat signs such an agreement, we no longer have any claims against Israel. So he cannot sign that, yet he knows that that is what Barak wants him to do. In a sense that’s what he’s being kept alive to do. Only he can end the conflict, only a Palestinian leader.

NS Having said all of this, your own position, I think, has always been that there couldn’t be a geographical solution anyway, even if it was possible to get sovereignty defined in terms of land, but the scenario you lay out …

ES No, I am prepared in principle, if it can be done, to have two states. If there is a clean separation between them, in the sense that one state is Israel (entirely Jewish with the exception of the Palestinian minorityöthat’s where the problems begin because no state is entirely one thing or the other) and another one which is largely Palestinian in which there are a certain number of Jewish residents (people from the settlements who don’t want to leave and can’t be made to leave) who will then have to stay there under Palestinian jurisdiction. The present agreement suggests that they can stay there extraterritorially under Israeli jurisdiction in a Palestinian state. I mean, that’s mad. So, in theory I’m not opposed to two states, ultimately moving towards one state, because the dimensions we’re talking about are so small. The facts, on the ground, are as follows: between Ramalla in the north and Bethlehem in the south, there are approximately a million people living now, Arabs and Jews roughly equal. There is no conceivable way that they can physically be separated without apartheid, in other words, unless you say that if you are of this religion you have these rights and if you are of that religion you don’t have them, which is the present arrangement. So that’s why I say we should have a state in which all citizens have one vote, the way the South African model worked to end apartheid. Failing that, you’re going to have a perpetuation of the conflict in one form or another. That is my educated guess.

Cindi Katz And it sounds like that is the way it’s going to go, in terms of the geographic imagination of the two peoples coexisting in one state space ...

ES Yes, well they are already doing that.

CK Right, but with legitimacy for both …

ES One is the coolie class, the underclass, and you can see them marked by, for example, if you go to some of the big Israeli settlements around Jerusalem or Qiriat Atumba or Ma’ahat Aldumin, etc, you walk or drive in the streets and you see that the people who are carrying the water, the people who look dirty, who have obviously been working in the fields, as gardeners let’s say, or cleaning the swimming pools, are Palestinians. They are the hired help. And if you go to restaurants inside Israel in Haifa, in West Jerusalem, in Tel Aviv, the waiters are all Palestinians. So it’s not just a figment, it’s not just a theoretical statement, you can actually see the coolie classöin the different complexions of people’s faces. Where you don’t see it so much are the areas of Israel where Oriental Jews live, who are in fact Arabs. And there it would seem to me there is the potential for some important political change. NS The way that you’ve responded specifically about Palestine today is a bit at odds with the more general argument that I think you’ve been making, especially the past two or three years, concerning the impossibility of territorial division really solving the conflict. ES Oh, I’m saying that. I’m not changing my mind. I believe that, I’m simply saying that if one’s to follow the logic that is currently in place, which seems to be that of territorial separation, and I guess the word is partition, I think that it can be made to happen. But it can’t, I don’t think, be made to work. That’s all I’m saying

NS There’s a broader set of geographical issues. The question of Palestinian nationalism has been alive since before 1948, but operates now in the context of a post-cold-war world. One of the responses to so-called globalization has been nationalism of different sorts, and there are a number of questions that get raised in that context. On the one hand, there is the dire historical warning from somebody like Franz Fanon about what national liberation struggles would get to do or would do to themselves when they got into power. But the other response to globalization has been perhaps more optimistic. There is discussion of a new internationalism that emerged even before the Seattle uprising. How do you think the question of Palestinian nationalism, given what you just said about the possible trajectories for Palestine, how do you think Palestinian nationalism will fit in that larger global context?

ES Let me say a little word about the dialectic of national liberation that Fanon talked about. Namely that unless there is a transformation of consciousness, nationalism itself will simply lead to another repressive form, that is basically a copy of the old colonial form. This has already happened. The Palestinian Authority is a kind of degraded reproduction of Israeli and before that British and before thatöthe order is, Palestinian, Israeli, Egyptian, Jordanian (Egypt in Gaza and Jordan in the West Bank) and before that Britishöcolonial control. So the Palestinian Authority is just another version of that, in that it is mostly made up of security services. There are more people working there than in any other sector. 60% of the budget goes into the bureaucracy and the security services, 2% goes into the infrastructure. It is totally unproductive and above all it’s repressive. There was just a report by Amnesty, that there have been more reporters, television stations, journals, magazines, and newspapers shut down by the Authority than at any time before. So that’s the nightmare.

Now, in the larger context, it’s difficult to jump from there to questions of globalization, as raised by celebrants of globalization like [New York Times reporter] Thomas Friedman who’s going around telling everyone that salvation is at hand. Unless you have a certain sense of national self-definition and realization, a place where you don’t feel yourself being repressed, then you have to have an intermediate step. You can’t just jump to a kind of global or globalized or cosmopolitan or internationalist consciousness easily. This is the case for most Palestinians since they are repressed and persecuted and singled out by virtue of their local identity as Palestinians. Even somebody of my son’s generation, who has on his passport my name, is singled out when I am described as being born in Palestine. He gets selective treatment at any border that he might go to whether it’s in the Arab world, Israel, or Western Europe. So global consciousness in our case is, unfortunately in my opinion, going very far in the direction of small enterprises in the form of NGOs. NGOs are part of an international network, funded politically, in the case of Palestine. There are 65 or 66 research institutes, a dozen women’s groups, more NGOs than I can tell you because I can’t count all the outfits on workers’ rights (my son worked in one of them “Democracy and Workers’ Rights”), others for village health systems, on folklore and folk customs and dress. If that’s part of globalization from below, fine, but it’s not a substitute for a political movement. That’s the great problem and that’s what is happening. People are necessarily using these NGOs, especially the professional middle class, which has to worry about its children’s education, getting a passport since you can’t move from one section of Palestine to another without Israeli permits. All of that can be facilitated by an NGO umbrella but unfortunately all of the NGO organizations are plugged into the so-called peace process. So if you look carefully in the preamble of any grant it says that this has to be done within the context of the Oslo agreement.

So that’s what’s happening. Other than that, Palestinians travel and there is now a generalized Palestinian consciousness, which is emerging from the diaspora, that is quite powerful. And it is necessarily international because Palestinians live everywhere. There is a large and powerful movement beginning in this country, there’s one in Western Europe, every Arab country has one. But it’s inchoate, it isn’t really focused as a movement and it doesn’t play a role except for one thing, namely return. The idea of return is central to Palestinian life in the global geography. So wherever you go if you ask a Palestinian where are you from he might say I’m from Um el Shahan, and I will say I am from Jerusalem, so that the old geography is being maintained that way. Beyond that, there isn’t very much.

CK But the interest in return gets subverted by the state process, which doesn’t allow for any return. So the question of Palestinian liberation …

ES Yes. Liberation is a word that you don’t hear any more. Go back to the early part of this year in Lebanon. This was the only example in our recent history where territory was liberated from the Israelis namely in South Lebanon thanks to Hezbollah. Now one may not like Hezbollahöit is a religious organization and so on and so forthöbut they are the only Arab group, army, whatever you want to call them, who was able to get the Israelis out. And there the word resistance mukhalam was used along with liberation, but it has a brief flowering in that context and only in that context. One of the things that is very interesting, I think, is the discursive environment where words like `liberation’, words like `planning’, words like `the common good’ have all lost their meaning. They may now mean the tyranny of the state; for `the common good’ Arafat might come and close your radio station down because you’ve been disloyal, and disloyalty in the face of the Zionist enemy means you lose your license to broadcast. In other words you can’t be critical. And that’s what nationalism has become. But the idea of liberation doesn’t exist anymore. Arafat says in his speeches that he’s going to liberate Jerusalem but there’s no evidence that he’s doing anything about it except giving speeches.

So that whole context, I’m afraid, has disappeared as a result of the disappearance of the Left. There is no Left to speak of. There is a new force, which is vaguely considered on the left, namely Hamas, the religious Islamic forces. They represent resistance, but they can’t be said to be on the left. So liberation has in a curious sort of wayöI can’t say diedöbut has simply gone under, gone under a sand dune. People are not talking in those terms. They are talking more in terms of globalizationö linking to the global economy. Much of the language of the Authority, for example, is very much like the following: we plan to turn this place into a Singapore, forgetting that there already is a Singapore, not only in Singapore, but also in the Middle East. It’s Israel! Israel is Singapore. The new language of the Authority is the language of computers.

There was an attempt to use the global system for the purposes of liberation, instituted this year in a refugee camp just south of Bethlehem called Dahesha. It’s inside the West Bank, it’s under the Palestinian Authority, but it’s made up of people from near Bethlehem but on the Israeli sideöpeople who were driven out in ’48 and their descendentsöand those people came to this area near Bethlehem, just a few miles away, after being driven out by the Israelis. They established this refugee camp under UNHCR [UN High Commission for Refugees], at the United Nations, and of course people began to build there, and now we’re in the third generation, so you have high-school kids in the camp. A group of camp residents last year decided that there was one way to break out and that is to establish something they called Operation Ibta’. Ibta’ in Arabic means creativity, like the creativity of a writer or an artist. And in that camp 640 C Katz, N Smith they bought computer terminals and trained children to be able to use them in order to communicate with other children in other camps in other parts of the Middle East. So it was the first time that the refugees were communicating amongst themselves. And not only that, one of their projects was for the children who lived in Dahesha who therefore were able to traverse the green line, go into Israel, visit their villages and describe their villages on the computers to other refugees. And so the circle grew.

On August 26th the site where these computers were held was invaded and destroyedöall of them smashed. Who was behind it? You could think of at least three or four parties who would be interested in destroying this project. One of course would be the Israelis, because what was growing was in fact a kind of consciousness that militated against the divisions and the partitions that have been imposed on people and that was what the peace process was trying to do. Another, is the Authority itself, because here was this new condition, namely return and unification of the people, a sense that we are one people no matter where we are, actually being realized and embodied in this activity and so it had to be destroyed. And so on down the line. You can imagine the Jordanians were not very happy about this, nor the Egyptians. So here is an example where the global connections can be seen positively in a kind of primitive way, but it’s also very threatened.

NS One of the attractions of your work for many of us who are trained in geography, comes from your Conrad (1) work, which is much more literary. From Orientalism(2) through Culture and Imperialism(3) and into your later writings, an incredible geographical sensibility is apparent. That is obviously very attractive to us, but it’s also something that is not easy to connect to. It is a geographical sensibility that’s developed even in your life as you’ve lived in the United Statesöa country with probably the least developed geographical sensibility in the world. The wider populace has a very poor geographical imagination. Where do you think your geographical sensibility came from? How do you account for the fact that there is an extraordinary recognition in your work of the politics of geography and the geography of politics?

ES Well I think partly it was historical accident. I seem to have lived and come to consciousness in a period when the great immediate postwar transformations of the world I lived in were beginning. First of all, the displacement of the Colonial authorities. I watched the evacuation of Egypt and Palestine by British soldiers, and in Lebanon, which is where we spent summers, in Lebanon by the French. I remember very clearly, the shock of seeing a Senegalese soldier on the streets of Beirut. It was quite a sight, a Zv’ar, in the blazing hot sun and in his beaver hat and red fur, and I had to wonder what was going on?

NS What were they doing there?

ES What were they doing there, exactly! This made me very conscious of the displacement of people, especially people I knew. The major thing was ’48 when a family that was scattered throughout all of Palestine was suddenly no longer there and I knew no one in Palestine. They were all somewhere else. That was very important. Also as I discovered in my memoir, I developed a sense of being out of place, never being able to be in a place where I felt completely at home. I then realized fairly early that I could never be at home, that it was impossible to return to places, that when one left one left, more or less, that it was an existential departure that could never really be restored. And then I began to be attracted to those kind of experiences in what I read and in what I wrote. Hence Conrad, who was a tremendously important kind of peripatetic, who embodied the sense of exile, but also strangely enough even the notion of philology, which I was very early interested in as a literary critic. There is a wonderful book by a Hispanist at Yale called Rosa Menocal called The Shards of Love, (4) and it’s a study of the lyric. And she argues that the lyric, as well as the rise of philology, are based upon exile; that you only write about things in a lyrical way if there is a sense of distance and loss and dispossession. That the great philological tradition historically (going back as far as Dante but certainly coming through into our century to Auerbachöpeople to whom I’ve always been attracted) always excluded exiles, the people who had used words where geography was cruel.

(1) Said (1966).

(2) Said (1978).

(3) Said (1993).

NS Let me push you on this. There are immigrants who come to the United States with a well-developed spatial imagination, either as exiles or as voluntary. But for many of those immigrants the geographical sensibility either gets lost, curtailed, diminished, or pushed off into a sort of nostalgia for the old country wherever that is. And that never happened to you, in fact the opposite happened, your geography has become stronger in your work. Why is that?

ES Because geography, in a funny way, is the only way that I can coherently express my history. The expression of history for me is always through the geography and not the other way around. Geography expresses the basic constituent parts of a past, I find the system and a consensus against which I’ve always warred. As I grow older I’ve become more rebellious and more unwilling to accept the power of the consensus as expressed through the geographical: that is to say the occupation of space, the attempt to transform space from one thing into another. It goes back to the Palestinian experience for me. This was a land called Palestine and suddenly it became a land called Israel. The new leaders said there was nobody there, or even if they were there, they really weren’t the people of the landöGolda Meier 1969. Those were great transformative movements in my imagination, holding onto geographyögeography as a part of history that has been denied. So geography is the expression of history rather than of something else. You might say it’s the ontological material with which I find myself working more and more.

CK I’ve always appreciated that in all of your writing and I had a visceral experience of that in Jerusalem, where I had resisted going for anti-Zionist reasons, but El Al was the only airline that had a youth fare when I first went to Africa, so I ended up staying in East Jerusalem, and only going to see Jerusalem, not Israel. But I was really willing myself not to be interested, but of course it was this extraordinary place and I was walking on Solomon’s Stables and I had this embodied experience of the layers of history in that space and all of the different people and all of the struggles. It was almost like feeling the struggles in a way that I imagined I was going to feel when I saw the pyramids, which were beautiful, but they are architecture. Jerusalem embodied a more social experience of geography as history.

ES Yes, well there are certain kinds of cities, obviously like Paris, where everything is separated out geographically and everything seems to be framed and highlighted for ways that you could look at it …

NS Monumental …

ES Monumentalized, well-framed is the best way I know to describe it. The monuments are framed, so that in a sense they lose their past and they become transformed into something which is to me an assault on the eye. And obviously it’s supposed to make you feel insignificant. Paris is a lovely city, but the other kind of city that I feel much more at home in, even more than Jerusalem, is a city like Cairo. With all of the levels, it is a city that is unimaginably rich, much richer than Jerusalem, there is no comparison. But there it’s all mixed up, it’s untidy, it’s dirty. You can’t get an aspect of the city where you can say “there it is”. It can’t be framed because there’s always something coming in the frame, some shard of the past, some fragment, there’s something necessarily incomplete. It’s always being built, built over, rebuilt, torn down, etc. but nothing ever disappears. Bits of it are always peering out at you. And that I find somehow consonant with my own experience of geography, that geography is always significant and there is always something taking place there that has taken place, will take place, the physical signs of it are there to be read.

(4) Menocal (1994)

CK Does New York give you that feeling?

ES Not so much, but New York in a certain sense theoretically does, in that it is a city in which you know that everybody that you see isn’t from New York. A large number of people have come from elsewhere. So in a certain sense, you might say that New York is an end result of all of these kinds of warring and competing geographies, where they’ve sort of spilled out into it.

NS Let me pick that up, because your memoir Out of Place, (5) makes a very eloquent case for how your own physical displacement and your autobiographical mobility, both physically and metaphorically, gives you this constant sense of homelessness, of being out of place. And yet reading it, I was thinking partly about New York and thinking you’ve been here for almost forty years. Here is a place and an episode in which you have placed yourself, in one sense found a place. And reading through the memoir there was one point I remember where you said that you actually did find a place for yourself in New York, yet elsewhere you insist that you feel alienated from and in New York, never quite at home. There seems to be a tremendous ambivalence about New York.

ES Oh absolutely, tremendous. Because I mean, New York is also the shadow of its former self. It has become the center of world capital. One can’t really not see that. But it’s also a place, as I said in the introduction to this new book of mine, that had an important history, a disappearing history, of radical agitation, radicalism in the arts, radicalism in politics, radicalism in thought. And it’s all slowly being ground down so to me New York is a kind of endless contest between how much can be homogenized and gentrified and swallowed up, and how much will resist it. And I think there is quite a lot of resistance, if you pay attention to it. If you don’t pay attention to it, then the city just seems like one undifferentiated thing.

CK You just see the center.

NS There’s another sort of silence I think in Out of Placeömaybe New York isn’t a silenceöbut it also struck me that the process by which you became increasingly politicized, before but especially after 1967, and became involved in Palestinian politics that was also an episode in which you were searching for a political place. Of course you’ve since moved away from at least an institutional connection with the Palestinian National Council, so you could argue that you have experienced a continuing displacement even within Palestinian politics. But there is an emplacement too, wasn’t politics also a means of finding a place? I almost expected a second volume: after Out of Place, perhaps Back in Place?

ES No, because I was always, I think, an outsider even in that movement, if that’s what you are talking about?

NS Yes, that’s exactly it.

ES I always felt myself to be critical of it, and not willing to become a member. I was never a member of any of the political parties. I was one of the very few people who was not a part of Fatah. I was a member of the PNC, but I was an independent member, I didn’t have any political affiliation. I was certainly courted by a number of groups who wanted it, but I felt that to become completely co-opted would mean a kind of emplacement and loyalty and, how shall I put it, assent, that would preclude any form of dissent. And I preferred to maintain that, even though, one could argue, and I certainly argued to myself, it was a kind of irresponsibility. Maybe I should have really submitted to the notion of discipline of a political movement, which many people have of my generation. I never did it, I never had it. I was always on the outside looking in and occasionally lobbing things into it to make noise and to try and stir things up. So I couldn’t write a volume like that because it would be too anecdotal, it would just be a series of stories.

For me the real engagement was in my work, and also, it would be too long a story ever to tell, but the different kinds of solidarity you build with people, all over the world. My travel was very important to me, when I went to South Africa, to India, to different parts of Europe. That was all part of building solidarity, where it was important just to keep Palestine in focus, the whole Palestinian cause and all it meant. I don’t mean just Palestinian nationalism, but the whole notion of dispossession, and exile and imagining a place and leaving it and coming back to it. How would you come back to it? All of those questions struck me as very serious, but they were slowly being dissolved in this enormous sentimental kind of thing, which on the one hand Zionism has always been, but also all the other kinds of nationalism and identity politics. I wanted by all means to save myself from that, to save the things that meant something to me. I didn’t want to get involved in that.

it wasn’t just Zionism because there was the Egyptian revolution in ’52, the Lebanese civil war. I mean Palestine obviously plays a role of some sort in all of them. I’ll give you an example, quite extraordinary. Just the other day there was an obituary in the New York Times, which I cut out. I don’t quite know why.

CK I agree. We need a kind of politics that always and again reinvents itself, and does so today against globalization and the homogenizing soup it implies.

ES Yes, but you need to see the problem too. I find myself now at a kind of strange impasse, because one feels very much alone, if what you’re looking for is a movement. The problem is there aren’t any movementsöthere are currents, there are attempts like Seattle, which you mentioned earlier, like the Intifada of a few years ago, that are not quite political movements, but suggest the beginnings of one. And I think we are very much in that problematic area, where we have emerging what Bourdieu calls, for example, a collective intellectual. There are a number of us, you knowöyou can point to Chomsky, to Bourdieu, you can point to Howard Zinn and younger people and their equivalents in England, like Stuart Hall, these people of an older generation who provide material for a younger generation to begin the work of a kind of reemerging Left, which has disappeared. But I wonder if it’s enough. There isn’t an organized force yet that can take on some of the challenges of post-cold-war globalization politics now. This is the problem.

NS Let me pick up on the question of your politicization on your way into, eventually the Palestinian National Committee. You didn’t really tell that story in Out of Place and I wondered if there’s a short way of telling how you were radicalized. Was it just 1967?

ES Yes, there is. Well 1967 in New York, was probably the most shattering experience in my life, because I was surrounded on all sides by people who identified with the Israeli victors. Walking down Broadway, I’ll never forget this, on 112th or 113th Street there was a market there, and somebody called out, “How are we doing?” on June 6th or June 7th. In other words, how are we doing it being our team. The other part of it was not being able to say anything. There was simply no place to say it and nobody to say it to. At the end of that year, I was asked to write something by a friend whom I hadn’t seen since the middle ’50s, you know, ten or fifteen years earlier. And he was putting together a book, a special issue of a magazine that later became a book, on the Arab ^ Israeli War of 1967 from an Arab perspective. He asked me write something, something about literature. And all I could do, because I didn’t know enough about the literature (the portrayal of the Arab in American literature is not something I was either interested in or that I knew much about), was write about the portrayal of the Arab in the media, and that is really the origin of Orientalism. That essay, called “The Arab Portrayed”, which I think is in the reader that was just put together,(6) was the origin of it. And therefore it became my political and intellectual task to resituate the Arab. Here is the geography coming back. I had to rewrite a geography that was, let’s say more authentic, I don’t mind being foundational about it, than the one into which Arabs were being transposed. It was always a male imposition, Arab women were always cast as entertainers, dancers, exotic women, “come into the Casbah with me” that kind of thing. The basic assault was on the man, and the man was always a kind of degraded, obscene figure whom it was a pleasure to destroy. It’s still going on!

It’s still going on, today. How many movies have you seen that just take the Arab as the kind of person to be killed. And so out of that grew a desire to somehow engage politically with all of the means at my disposal. And the second step, was to return to the Middle East to a place I had never been, Jordan. I lived in Palestine, and Lebanon, and Egypt, but Jordan was a little bit to the east and a lot of my family was there and some friends. After ’67, from America, Palestinians, one in particular, went to Jordan and signed up in the movement and I went to visit him, just to see what was happening. And that’s how it began. I saw that there was a movement. I mean it was physically there to be seen. And I was there during Black September in 1970. I went twice, ’69 and ’70, and I felt really engaged. So there was always a kind of back and forth, which was important for me. I never felt the need to stay in one place, but actually to literally move back and forth.

My mother lived in Beirut through the entire siege so that was a very important, also geographical, experience. It was a summer of extraordinary activity. I must have given five talks a day, traveling all the time, and in the back of my mind was the fixed horror of the siege. The Israelis turned off the water, and I rememberöI’ll never forget this as long as I liveöduring that summer the USA vetoed a resolution passed by the Security Council to let humanitarian aid, mainly medicine, into Beirut. And they vetoed it because it was `one sided’. That was the phrase usedöastonishing. In any case, throughout all of this there has been a geographical universe that has really been in my mind, in which I’ve worked in and out of constantly. It’s very, very powerful. It’s hard to describe it.

CK One of the things that I got from reading Out of Place was the space of childhood that Jerusalem was for you. You didn’t really live there in terms of your everyday existence, which was in Cairo, but it was this place that you went, where your family was, where your history was, where your family’s history was, and that …

ES And all of my family was there. I didn’t have any family in Cairo except my maiden aunt, Aunt Melia. She was an extraordinary woman. It’s funny that Cairo was only the place that I lived and so on. It was always the place that was the exception. The kind of rule, as it were, was Jerusalem.

CK But it also reminded me of the way I feel about Mohegan, a lake community in New York State where my family went, where my grandparents lived, where we went for the summer. It was this free timeöand it just struck me, this may be completely off the wallöthat 1948 was also when you became an adolescent, so that the moment when you’re excluded from the place that’s really the deepest home is also the moment of your own puberty. Does that infuse or charge the politics that you have since?

ES It must have, it must have, but cumulatively and over time. As I describe it in Out of Place, it was a kind of dawning realization that so much of the lives led afterwardsö including my own which involved this personally horrendous separation from the Middle East in 1951 when I came hereöwas the sense of a tremendous scattering of all of us away from our habitual life. So it was a geographical alienation, but it was also, on another level, an alienation from familiar ways: the way people, for example, used to measure the prosperity of their lives in the number of barrels of olive oil that they would consume per annum. That kind of measurement no longer had any meaning. And I was impressed also that as he grew older, my father (it’s strange how my father whom I saw obviously more often in places like Cairo and Lebanon than I did in Jerusalem) he became more of a Jerusalemite in his accent, his habits, and his orientation. It was very striking, even my mother was very irritated at it. It was as if, she said, “why is he speaking that old dialect, he left it fifty years ago and now he’s coming back to it?”

So, in a sense it was partly the alienation and the sense of really being disrupted and the moorings cut off and we were drifting. It’s a very, very frightening feeling. And in our case it wasn’t just one displacement, but two, three, four displacements of that sort. Consider my uncle, my mother’s brother, whom I remember visiting when he was working at the Arab Bank in Nablus. A year later I saw him in Alexandria; shortly after that he left Alexandria and came to Cairo for a brief period; then he left Cairo for Baghdad and after the 1958 revolution in Baghdad he ends up in Beirut; the civil war begins in 1975, and by the late ’70s he has to leave because it was impossible to live in West Beirut where most of the bombing was taking place. He’s now in his late eighties and he’s living in Seattle, in a suburb of Seattle even. That sort of thing multiplied many times has a very powerful effect on you. And it really shakes your faith in anything actually resembling continuity. Until recently, one of the nightmares I had, actually a recurring nightmare of my earlier life, was that whole institutions would disappear. That a bank would close, a school would disappear, a university. For years I didn’t think that Columbia would endure for another yearömaybe it won’t be there tomorrow. It’s very strange. That sense of discontinuity is very powerful.

CK I didn’t mean, in any way, to trivialize it by comparing it to my example.

ES No, no, no.

CK But it was just that it struck me that at that particular moment that world politics, Zionist politics, wrench …

ES No, no, it wasn’t just Zionism because there was the Egyptian revolution in ’52, the Lebanese civil war. I mean Palestine obviously plays a role of some sort in all of them. I’ll give you an example, quite extraordinary. Just the other day there was an obituary in the New York Times, which I cut out. I don’t quite know why. A chap who was in my class at Victoria College, his name is Gilbert de Botton (his son is Allain de Botton, who wrote a book on the Consolations of Philosophy, he wrote a book about Proust, two or three novels, all in his twentiesöobviously a prodigy of some sort).(7) Botton was an important character at Victoria College. He was probably the smartest kid in the school. I knew he was Jewish, but I asked him, “Where did you get the name fromö de Botton?” And he said, “Well we’re from Belgium.” He then left, as did I in the early ’50s. I saw him once when I was in Princeton. I didn’t know where he went to, but I ran into him by chance at Princeton when I was a Junior. He came to the library and said he was working in New York. When I pressed him a bit, he said he was working for the Israeli mission to the UN. He then surfaced in the early ’80s as the head of the Rothschild Bank in New York. Later he goes to London and he becomes a major financier, and he died last week. He had sold his business a month or so before for 650 million dollars. He was always a chap from my past. In a review of my book, written in the New York Review of Books, Amos Elon, the Israeli writer, reveals that de Botton’s mother was the head of the Mossad in Cairo, and that when she died she had a state funeral.(8) So all of this history that I had with de Botton as a Belgian is suspect. According to the obituary, they were Alexandrian Jews, Oriental Jews. Extraordinary. So geographical provenance is itself a problematic thing: there are always hidings, and what’s revealed and what isn’t changes depending on where you’re really from. And where you’re really from is attached also to ideological issues, it’s not just a matter of saying I am from Middletown, Connecticut. It’s not that simple.

CK When you mentioned the The Shards of Love, which sounds wonderful, and the relationship to philology, I immediately began thinking in terms of minor literature, which obviously you know about. Here we are geographers asking you about literary theory...

ES No, it’s all right go onö

CK … but I wondered if that idea of minor literature makes any sense to you?(9) Does it help you understand your own work as a writer, willfully out of place, using a learned language but using it to push the limits of that language itself?

ES I think that the concept, that Deleuze and Guattari mobilize in the whole business of minor literature, turns out to be a description of a much larger and more influential phenomenon than they suspected. Of course they were talking about people like Kafka, who was not German, using German. But let’s take a few of the major literatures of Europe. Look at English literature and the Irish component in that. There’s very little left that you can say is native English, I mean Burke, Swift, Goldsmith, Mariah Edgeworth, and Sheridan. They were all Irish. And then when you come to someone like Joyce, Joyce much more than any of the others except Swift, really transformed the language, creating a new language in Finnegan’s Wake. So it’s not just a question of a minor literature it’s really that the major literature is sort of unhousing itself in the process of its creation. I think it is true of Italian literature too, and Menocal talks about this. Dante, for example, was an exile too, and his attempt to create the dolce style nuovo, (10) really worked out at the peripheries of the literature. So I think we have to change the landscape from a discussion of dominant to peripheral literatures. A series of assembled peripherals is really what we have, peripherals that work in an elaboration that is simply unceasing. I think what we have is a new perspective, and we’re able to see all literatures working in that way instead of major versus minor, which is the theory. You understand, I don’t think that the dichotomy is really operable. I mean you can read everything in terms of digressions rather than the main course and then there’s a digression …

(7) De Botton (1995; 1997; 2000).

(8) Elon (1999).

(9)Deleuze and Guattari (1986). See also Katz (1996).

(10) Dolce style nuovo (sweet new style) refers to a style of love poetry that Dante, among others, started in the late 14th century. In attempting to make the object of love more divine, the new style challenged prevailing and more erotic poems associated with the Sicilian and Provencal Schools, which treated love as carnal and mundane

CK Well it sounds like that kind of excess that you see in Cairo…

ES Yes, absolutely. That’s what it is. In other words, it’s not the center that really defines it, but it’s really the peripheries, and then you find that’s all there is is peripheries. Everything is an elaboration of something else. And it’s very close to my interest in music for example. What I’m interested in in music is really counterpoint. I mean, the thing in counterpoint is that the center is defined not, you might say, in a linear way, but in a horizontal way so that the outer limits are just provisional. What could be the main voice let’s say in the soprano or the bass, immediately transfers to one of the middle voices, so it’s never a stable stateö“here is the topography and this is the center and everything else is periphery.” I think we’ve changed now, more or less forever… I think.

CK Well that anticipates my next question, which is about how music works for you spatially…

ES Well it’s very strange. There are composers whom I can’t listen to for that reason. And that is one of the reasons I’m so impressed with, and have been for a long time, so imprinted with the work of Glenn Gould whose whole work was a kind of geographical realization of music so that you can actually see it on different levels. And his performance, let’s say of a Bach fugue, enables you to actually see the fugue as a rhetorical device whose basis is actually geographical. Why? Because the notion of invention goes back to the Ciceronian concept of invention which goes back to the art of memory, and you remember things by placing them in different places. So invention is the art of walking around in a place and finding the things that you need for the current composition and then putting them all together. So it’s ultimately a spatial rather than a temporal phenomenon, which is the way that music usually is interpreted. Of course it’s both, but the geographical emphasis on this contrapuntal scheme is so interesting to me. That’s number one.

The second part of it is the resistance of music to ordinary solicitations of argument. And therefore the need to look elsewhere for the argument, not in saying it makes this point and goes from a to b to c to d and then you’re home. No, there’s something else going on and you know you’re really always looking for it in different aspects of music. Sometimes it’s a rhythmical question that might settle the issue, at other times it’s a tonal question, a question of timbre, different kinds of organizations all of them leading me constantly into the language of music. And searching for an answer I know can’t ever come, but there’s a kind of tension between music and sound, you might say, that’s permanent, which is deeply interesting to me.

NS I have a couple of other more general questions. I wanted to ask you probably fairly obvious questions about Marx and Marxism. And the reason for asking this is not maybe just the usual question of asking you what is the influence of Marx and your ambivalence and all the rest of it. But, within geography since the 1970s, Marx’s work has really had, I think you could argue, a more important effect than in any of the other social sciences. Part of that was that geography was so underdeveloped as a discipline. Geography as a discipline had so little sophistication in terms of social theory that when Marxist work hit in the early ’70s it just took the discipline by storm. And by the early 1980s, Marxist work dominated the research frontier.

ES Because of you, you and Harvey.

NS Well Harvey is obviously one of the pioneers, but there were a number of people, Jim Blaut, Dick Peet, Doreen Massey in Britain and others, Suzanne Mackenzie in Canada and so on. But also a bunch of graduate students too. Marxism has had this peculiar effect in geography, and the last twenty years has been a process of the deepening of that Marxist work, but also the emergence of lots of critical forms of social theory, much interdisciplinary work around, and in some ways responses to, Marxist work. And so, you obviously for us are a figure who on the one hand has a deeply geographical sensibility and on the other is heavily influenced by Marxism but is also critical and ambivalent about it. I wonder if you’d want to talk about the importance of Marx to you, but keeping the geographical sensibility in the front of your…

ES Well, I’ve never really confessed this, but I have to say that the influence of Marx on me was mainly through his minor works. That is to say, whatever I really most powerfully was impressed by were things like the Eighteenth Brumaire, the Class Struggle in France, that is to say not the major theoretical works, neither Capital nor the Grundrisse.

NS Why is that?

ES Because of my antipathy toward what seem to be systems and major theoretical statements of some sort. I’m enough of a kind of fox, as opposed to a hedgehog, to always feel very uncomfortable with that and to look for exceptions to it, and to note the things in the system that simply are not touched by it. I mean, imperialism, colonial practice, racial theory, the family, nationalismöall of things that meant so much to me. Even aesthetics in Marx are kind of underdeveloped and understated. So, that’s number one. Dissatisfaction with that, and tremendous pleasure in the aspect of Marx that was most like someone like Swift. Swift of course was very right wing, Marx very left wing, but the pamphleteer, the rhetorician, the ironist, the deployer of extraordinary rhetoric in order to illustrate a situation in an unforgettable way. In the Eighteenth Brumaire, the putsch of the people around Napoleon III is an unforgettable spectacle, very vivid in Marx, along with the irony and anger. It was all of these perhaps minor aspects of Marx that influenced me.

And then second, the aspect of Marx that influenced me the most were his disciples. I was transformed by my reading of History and Class Consciousness, (11) just as I was transformed by my reading and teaching of The Prison Notebooks(12) and later of Adorno, especially his musical work. So it’s the unexpected aspects of Marx, rather than the systematic ones, which are very much part of what I would call my secular outlookö the resistance to overarching theories that will solve all of the problems for you in some way and my unwillingness to give myself up to a paradigm. I didn’t want to be identified as a Marxistö“you’re one of us” that kind of thingöanymore than I’ve been happy being identified as a Palestinian. You understand what I’m trying to say?

NS There’s a pattern here, let me see if I can pull this out a wee bit more. In terms of your politics vis-a©-vis Palestine, you’re certainly heavily involved in political, public arguments around Palestine but you don’t want to go so far as to join `the party’. In terms of Palestinian self determination, the geographical question, you’re absolutely supportive of self-determination but you have at least an ambivalence about it being territorialized and fixed in place.

ES Which I know it has to be.

NS Right. And then with the Marxist question too, you’re very happy to be influenced by Marxist work, but you won’t go so far as to…

ES to be a Marxist …

NS … take on the systematic critique of capitalism in that rather larger theoretical way.

ES Yes.

NS There’s an argument that would say, that these are wonderful intellectual places to be, but at some point there’s a strategic essentialism that would have to come into place. That what you gain by staying outside of the territorialization of the state, the party as a fixation of politics, Marx’s critique of capitalism as a kind of fixation of the larger critical position, you give up too much refusing that move.

ES For me, for me, for me! Yes, I would agree with that. I mean, I feel it. But I somehow don’t feel that it’s… I mean, I think it’s an admirable summing up that you just gave, and the parallelism is absolutely true, but I’m not sure that it registers enough my dissatisfaction with the essentialism, with the strategic sort of giving up to the system in a way. Because I feel very much in those other things that you mentioned, on the other side. In Marxism and territorialization, for example, there’s a kind of orthodoxy, a kind of authority, and a kind of finality which I’m not prepared to recognize. I’m simply not. Insofar as one talks about recognitions and acknowledgments that’s not one I want to make at this point.

NS Having been in a Marxist revolutionary organization, I recognize exactly the trade off between the sharpness of the vision that you get from the active involvement vis-a©-vis the chopping off of possibilities.

ES Yes, absolutely. There was a time with people of my generation whom I admired, like Jameson, for instance. I haven’t seen him much really, but I’ve known him for about thirty years. I sort of envied it a bit, you know, that here’s a man who knew where he stood. To my way thinking he’s very unpolitical, he’s not politically engaged, but he’s a genius of speculation and systematic analysis on a very, very high level, and I found it tremendously exhilarating and informative to read him. But I remember the one time, he went to the Middle East and he came to Beirut, I arranged the trip and he went with several of my friends. They went and he came back and he was teaching at Yale at the timeöthis must have been twenty years agoöand he said for me this question is very simple. And I said, “Really? What is it?” He said it’s capitalism! Zionism is capitalism. And he gave one talk and wrote one article for the Yale News and he never talked about it again because it was solved, it was simple. All the energy and the people involved in the struggles, I don’t mean this as a criticism. I think it’s a temperamental thing. I’m temperamentally incapable of that kind of resolution. I’m always looking for what is unreconcilable, for what is unresolved, for what is in permanent tension. The idea that one could find the rest in a magnificent whole of some sort, I think like Adorno that the whole is the false.

NS But do you have to go that far? I mean isn’t it possible to take on more of… I mean for me, I would find myself in much greater agreement with you about the real problems of fixing the state, the problems even of party membership, which I have experienced personally, but at the same time I would want to retain a strong sense of the larger theoretical critique of capitalism that comes out of Marx.

ES Oh, absolutely. I’m very happy with that.

CK But I think you can have that with …

ES You can have that without fetishizing it. And I’ll tell you the honest truth if I may, I would find it impossible to distinguish the main elements of Marxism in the current situation if one were to do an economic analysis of globalization. I think the Marxist notion has been so transformed into something else that to call it Marxism would be a resort to a kind of fetishism in a way. You can say it all originates in Marx, yes, but everything really originates in Plato and Aristotle by the same token. Do you understand what I mean? We take for granted so muchöI doöin the current discussions of corporate, of finance capital that it’s obviously Marx. It’s like gravity, we don’t have to reinvent it, we don’t have to point to Newton and go through that whole thing. The discourse is advanced enough that I’ve absorbed it. And, perhaps more important, I feel a very powerful adverse relationship to capital. It has become, it seems to me, more clarified in its inhumanity and the destruction it has wreaked upon the poor countries, through the new world economic order, which is horrendous. But there I don’t think Marx is a tremendous help, I mean someone like Amartya Sen is much more interesting to me.

CK As I was listening to you I thought of a line in Out of Place that I completely related to, that you got from your mother a kind of agony about paths not taken.

ES Oh, absolutely yes.

CK And I share that although I’ve been able to say I am a Marxist and a feminist, but I think that when you say it’s a disposition in a certain way, that it’s not just looking back, but it’s the excesses or the messö

ES Yes, exactly. I find myself there much too long. CK I was just glad to see it said in such an eloquent way.

References

De Botton A, 1995 Kiss and Tell (Macmillan, London)

De Botton A, 1997 How Proust Can Change Your Life (Pantheon Books, New York)

De Botton A, 2000 The Consolations of Philosophy (Pantheon Books, New York)

Deleuze G, Guattari F, 1986 Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature (University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, MN)

Elon A, 1999, “Exile’s Return” New York Review of Books 18 November

Gramsci A, 1971 Selections from the Prison Notebooks of Antonio Gramsci edited and translated by Q Hoare, G Nowell-Smith (International Publishers, New York)

Katz C, 1996,“Towards minor theory”Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 14 487 ^ 499

Luka¨cs G, 1971 History and Class Consciousness: Studies in Marxist Dialectics translated by R Livingstone (MIT Press, Cambridge, MA)

Menocal M R, 1994 The Shards of Love: Exiles and the Origins of the Lyric (Duke University Press, Durham, NC)

Said E W, 1966 Joseph Conrad and the Fiction of Autobiography (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA)

Said E W, 1978 Orientalism (Penguin Books, New York)

Said E W, 1993 Culture and Imperialism (Alfred A Knopf, New York)

Said E W, 1999 Out of Place: A Memoir (Alfred A Knopf, New York)

Said E W, 2000 The Edward Said Reader (Vintage Books, New York)

Cindi Katz

Environmental Psychology Program, Graduate Center, City University of New York,

365 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10016, USA; e-mail: ckatz@gc.cuny.edu

Neil Smith

Center for Place, Culture and Politics, Graduate Center, City University of New York,

365 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10016, USA; e-mail: nsmith@gc.cuny.edu