On 17 May 1919 in Paris, three Indian Muslim leaders met the United States’ president Woodrow Wilson to make a case for the preservation of the Ottoman caliphate in Istanbul, and for the national self-determination of Anatolia as a homeland for Turkish Muslims. The Indians advocated for the independence of what they called ‘the last remaining Muslim power in the world’. Indian Muslim leaders speaking up on behalf of an Ottoman caliphate might appear to represent a global Muslim unity, but such a conclusion would be a mistake.

In fact, the details, arguments and ideals of the meeting reveal how incoherent and misleading the prevalent presumption is of any distinction between ‘the Muslim world’ and ‘the West’. The Indian Muslims made their case for Turkish independence by appeals to Wilson’s 14 points for peace. Their success in getting the meeting with Wilson owed much to their sacrifice as soldiers in the British army fighting and defeating the German-Ottoman alliance. Edwin Montagu, Secretary of State for British-ruled India, arranged the meeting because he believed that the British empire, as the biggest Muslim empire in the world, had a moral responsibility to listen to the Indian Muslim case for the preservation of the Ottoman caliphate. All three Muslim leaders asserting their spiritual ties to the Ottoman caliph – the Aga Khan, Abdullah Yusuf Ali and Sahibzada Aftab Ahmad Khan – were loyal subjects of the British Crown. Several Indian Hindu leaders joined the meeting, making clear their solidarity with their fellow Indian Muslim brethren and their support for the Ottoman caliphate.

This conversation at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 does not reveal a clash between an Islamic world and a Western world. It reveals one complex and interdependent world. Yet, consider Bernard Lewis’s influential essay in The Atlantic magazine, ‘The Roots of the Muslim Rage’ (1990): ‘In the classical Islamic view, to which many Muslims are beginning to return, the world and all mankind are divided into two: the House of Islam, where the Muslim law and faith prevail, and the rest, known as the House of Unbelief or the House of War, which it is the duty of Muslims ultimately to bring to Islam.’ Lewis left little doubt that this alleged ‘duty’ of Muslims meant violent means: ‘The obligation of holy war … begins at home and continues abroad, against the same infidel enemy.’ In spirit and substance, the Indian Muslim leaders meeting with Wilson in 1919 contradicts every single claim by Lewis. The Muslims were loyal supporters of the multi-faith British empire, cooperating with Hindus, and had fought against the Muslim soldiers of the Ottoman empire during the First World War. They did not see Westerners as any kind of enemy, and made their case for the Ottoman caliphate according to international norms about national self-determination and imperial peace.

Though he has been influential in US policy circles, Lewis did not come up with the idea of ‘a Muslim world’ distinct from a Western one. Since the Iranian Revolution of 1979, Western journalists and radical Islamists popularised the idea. In their view, contemporary Pan-Islamism draws on ancient Muslim ideals in pursuit of restoring a pristine religious purity. According to this account, Pan-Islamism is a reactionary movement, in thrall to ancient traditions and classical Islamic law. The peculiarities of Islam, it is always argued, compel Muslims’ religious affiliation to transcend other political affiliations. This Pan-Islamism not only survives but thrives in the contemporary world, and is a civilisational artefact deeply at odds with modern times.

Lewis might not have originated the idea of the Muslim world, but he gave it an intellectual polish, and inspired Samuel Huntington’s even more popular work, The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order (1996). ‘The struggle between these rival systems [of the Islamic world and Christendom],’ wrote Lewis, ‘has now lasted for some 14 centuries. It began with the advent of Islam, in the 7th century, and has continued virtually to the present day. It has consisted of a long series of attacks and counterattacks, jihads and crusades, conquests and reconquests.’

Such remains the dominant Western view of Pan-Islamism, expressed in the phrase common to punditry and journalism – ‘the Muslim world’. Yet, contrary to this dominant view of an eternal clash with the Christian West, Pan-Islamism is in fact relatively new, and not so exceptional. Closely related to Pan-Africanism and Pan-Asianism, it emerged in the 1880s as a response to the iniquities of European imperialism. Initially, the idea of global Muslim solidarity aimed to give Muslims more rights within European empires, to respond to ideas of white/Christian supremacy, and to assert the equality of existing Muslim states in international law.

he idea of an ancient clash between the Muslim World and the Christian World is a dangerous and modern myth. It relies on fabricated misrepresentations of separate Islamic and Western geopolitical and civilisational unities. Pan-Africanism and Pan-Asianism offer a better context for understanding Pan-Islamism. All three emerged in the late 19th century, at the height of the age of empire, and as counters to Anglo-Saxon supremacy and the white man’s civilising mission. Pan-Islamists in the age of empire did not have to convince fellow Muslims about the global unity of their co-religionists. By racialising their Muslim subjects with references to their religious identity, colonisers created the conceptual foundations of modern Muslim unity.

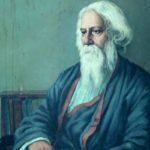

At the time, the British, Dutch, French and Russian empires ruled the majority of the world’s Muslims. Like Pan-Africanists and Pan-Asianists, the first Pan-Islamists were intellectuals who wanted to counter the slights, humiliations and exploitation of Western colonial domination. They did not necessarily want to reject the imperial world or the reality of empires. In their sensibilities, the leading Pan-Islamist intellectuals Jamaluddin al-Afghani and Syed Ameer Ali strongly resembled the Pan-Africanist W E B Dubois or the Pan-Asianist Rabindranath Tagore. Like Pan-Africanists and Pan-Asianists, Pan-Islamists emphasised that European empires discriminated against Africans, Asians and Muslims, both within empires and in international affairs. All three challenged European racism and colonial domination, and promised a better and freer world for the majority of human beings on Earth.

European colonial officers began to worry about a potential Muslim revolt when they saw how the modern technologies of printing, steamships and the telegraph were creating new links among diverse Muslim populations, helping them to assert a critique of racism and discrimination. Yet there were no Pan-Islamic revolts against colonialism from the 1870s to the 1910s. The alleged threat of Pan-Islamism made its first notable appearance in the West during the First World War, in part because the Ottoman and German empires promoted it in their war propaganda. Yet there was no Muslim revolt during the First World War when hundreds of thousands of Muslim soldiers served British, French and Russian empires. During the Second World War, Pan-Asianism was associated with the Japanese empire’s promises to liberate the coloured races of Asia from white hegemony. And in the aftermath of Japan’s defeat, the historic decolonising of Africa raised the profile of Pan-Africanism among European concerns.

By the 1960s, with the fading of the colonial world and its replacement by a world of independent nation-states, the political projects of Pan-Islamism, Pan-Africanism and Pan-Asianism had almost disappeared. They had, however, won many of the intellectual battles against racism, defeated colonial arguments of white supremacy, and helped to end European imperial rule. Disappointments about the failure of Africa, Asia and the Muslim world to become comparable in equality and freedom to the West also contributed to the declining status of the pan-nationalisms. By the 1980s, African and African-American intellectuals grew more pessimistic about the key Pan-Africanist dream of gaining racial equality for black people in the modern world, and making the whole of Africa prosperous and free. The Pan-African vision of uniting newly independent, weak African nations to create the necessary synergy of a federative global power and give them both liberty and prosperity has not materialised. Although there is still an international organisation – the African Union – it is ineffective, and far from achieving the goals of Pan-Africanism. The hopes of the Pan-Africanist generation, from Dubois to Frantz Fanon, for a future decolonised Africa remain a lost project for the next generation.

The first Pan-Islamists were highly modernist proponents of the liberation of women and racial equality

On the other hand, with multiple great powers such as China, India and Japan, the decolonised Asia of today would have made the early 20th-century Pan-Asianists proud. Yet 20th-century Pan-Asianism took a complex course. Japan’s exploitation of Pan-Asianism to rationalise its colonial occupation of China and Korea left many supporters feeling betrayed. Independent India’s foreign policy under the leadership of Jawaharlal Nehru showed a commitment to some Pan-Asian principles, which retained popular appeal at the Bandung Conference of 1955. This meeting of 29 Asian and African states, comprising more than half the world’s people, was the last major expression of Asian solidarity, and was later subsumed by Cold War rivalries and nation-statebuilding projects.

Pan-Islamism has also proceeded in a series of fits and starts over the past century. From Turkey and Egypt to Indonesia and Algeria, the idea of Muslim intellectualism and global Muslim solidarity empowered 20th-century nationalist leaders and movements. By the mid-1960s, the majority of the world’s Muslims had gained freedom from European colonial rule. The Turkish Parliament had abolished the Ottoman caliphate back in 1924, and by the 1950s that caliphate was almost forgotten.

Nearly a fifth of the way into the 21st century, however, Pan-Africanism and Pan-Asianism seems to have vanished but Pan-Islamism and the ideal of Muslim world solidarity survives. Why? The answer lies in the final stages of the Cold War. It was in the 1980s that a new Muslim internationalism emerged, as part of a rising political Islam. It was not a clash between the primordial civilisational traditions of Islam and the West, or a reassertion of authentic religious values. It wasn’t even a persistence of early 20th-century Pan-Islamism, but rather a new formation of the Cold War. A Saudi-US alliance began promoting the idea of Muslim solidarity in the 1970s as an alternative to the secular Pan-Arabism of the Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser, whose country allied with the Soviet Union. Any ideas of an ‘Islamic’ utopia would have floundered if not for the failures of many post-colonial nation-states and the subsequent public disillusionment of many Muslims.

The notion that Pan-Islamism represents authentic, ancient, repressed Muslim political values in revolt against global Westernisation and secularisation was initially a paranoid obsession of Western colonial officers, but recently it comes mainly from Islamists. Western pundits and journalists have erred in accepting at face value Islamist claims about Islam’s essential political values. The kind of Islamism that’s identified with Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood or Ruhollah Khomeini’s Iran did not exist before the 1970s. None of the Indian Muslims meeting Wilson, nor the late Ottoman-era caliphs, were interested in imposing Sharia in their society. None of them wanted to veil women. On the contrary, the first Pan-Islamist generation was highly modernist: they were proponents of the liberation of women, racial equality and cosmopolitanism. Indian Muslims, for example, were very proud that the Ottoman caliph had Greek and Armenian ministers and ambassadors. They also wanted to see the British Crown appointing Hindu and Muslim ministers and high-level officials in their governments. None would have desired or predicted the separation of Turks and Greeks in Ottoman lands, Arabs and Jews in Palestine, and Muslims and Hindus in India. Only the basic form of early 20th-century Pan-Islamism survives today; the substance of it has, since the 1980s, transformed completely.

The fact that both Lewis and Osama bin Laden spoke of an eternal clash between a united Muslim world and a united West does not mean it is a reality. Even at the peak of the idea of global Muslim solidarity in the late 19th century, Muslim societies were divided across political, linguistic and cultural lines. Since the time of prophet Muhammad’s Companions in the seventh century, hundreds of diverse kingdoms, empires and sultanates, some in conflict with each other, ruled over Muslim populations mixed with others. Separating Muslims from their Hindu, Buddhist, Christian and Jewish neighbours, and thinking of their societies in isolation, bears no relationship to the historical experience of human beings. There has never been, and could never be, a separate ‘Muslim world’.

All the new fascist Right-wing anti-Muslim groups in Europe and the US obsesses over Ottoman imperial expansion in eastern Europe. They see the Ottoman siege of Vienna of 1683 as the Islamic civilisation’s near-takeover of ‘the West’. But in the Battle of Vienna, Protestant Hungarians allied with the predominantly Muslim Ottoman empire against the Catholic Habsburgs. It was a complex conflict between empires and states, not a clash of civilisations.

The Hindu nationalism of India’s prime minister Narendra Modi promotes the idea of an alien Mughal empire that invaded India and ruled over Hindus. But Hindu bureaucrats played a vital role in India’s Mughal empire, and Mughal emperors were simply empire-builders, not zealots of theocratic rule over different faith communities. There are also Muslims today who look back at the Mughal empire in India as an instance of Muslim domination over Hindus. It is notable and important that anti-Muslim Western propaganda and Pan-Islamic narratives of history resemble one another. They both rely on the civilisational narrative of history and a geopolitical division of the world into discrete ahistorical entities such as black Africa, the Muslim world, Asia and the West.

Contemporary Pan-Islamism also idealises a mythical past. According to Pan-Islamists, the ummah, or worldwide Muslim community, originated at a time when Muslims were not humiliated by racist white empires or aggressive Western powers. Pan-Islamists want to ‘make the ummah great again’. Yet the notion of a golden age of Muslim political unity and solidarity relies on amnesia about the imperial past. Muslim societies were never politically united, and there were never homogeneous Muslim societies in Eurasia. None of the Muslim dynasty-ruled empires aimed to subjugate non-Muslims by pious believers. Like the Ottoman, Persian or Egyptian monarchs of the late 19th century, they were multi-ethnic empires, employing thousands of non-Muslim bureaucrats. Muslim populations simply never asked for global ummah solidarity before the late 19th-century moment of racialised European empires.

The term ‘the Muslim world’ first appeared in the 1870s. Initially, it was European missionaries or colonial officers who favoured it as a shorthand to refer to all those between the ‘yellow race’ of East Asia and the black race in Africa. They also used it to express their fear of a potential Muslim revolt, though Muslim subjects of empire were no more or less rebellious to their empires than Hindu or Buddhist subjects. After the great Indian Rebellion of 1857, when both Hindus and Muslims rose up against the British, some British colonial officers blamed Muslims for this uprising. William Wilson Hunter, a British colonial officer, questioned whether Indian Muslims could be loyal to a Christian monarch in his influential book, The Indian Musalmans: Are They Bound in Conscience to Rebel Against the Queen? (1871). In reality, Muslims were not much different from Hindus in terms of their loyalty as well as their critique of the British empire. Elite Indian Muslims, such as the reformist Syed Ahmad Khan, wrote angry rebuttals to Hunter’s allegations. But they also accepted his terms of debate, in which Muslims were a distinct and separate category of Indians.

To assert their dignity and equality, Muslim intellectuals emphasised the past glory of ‘the Muslim world’

The growth of European nationalisms also found a useful enemy in Muslims, specifically the Ottoman sultan. In the late 19th century, Greek, Serbian, Romanian and Bulgarian nationalists all began to depict the Ottoman sultan as a despot. They appealed to British liberals to break the Ottoman-British alliance on behalf of a global Christian solidarity. Anti-Ottoman British liberals such as William Gladstone argued that Christian solidarity should be important for British decisions with regard to the Ottoman empire. It is in that context that the Ottoman sultan referred to his spiritual link with Indian Muslims, to argue for a return to an Ottoman-British alliance thanks to this special connection between these two big Muslim empires.

In his influential book The Future of Islam (1882), the English poet Wilfrid Scawen Blunt argued that the Ottoman empire would eventually be expelled from Europe, and that Europe’s crusading spirit would turn Istanbul into a Christian city. Blunt also claimed that the British empire, lacking the hatred of Muslims of the Austrians, the Russians or the French, could become the protector of the world’s Muslim populations in Asia. In patronising and imperial ways, Blunt seemed to care about the future of Muslims. He was a supporter and friend of leading Muslim reformists such as Al-Afghani and Muhammad Abduh, and served as an intermediary between European intellectual circles and Muslim reformists.

Around the same time that Blunt was writing, the influential French intellectual Ernest Renan formulated a very negative view of Islam, especially in regard to science and civilisation. Renan saw Islam as a Semitic religion that would impede the development of science and rationality. His ideas symbolised the racialisation of Muslims via their religion. Of course, Renan was making this argument in Paris, which ruled over large parts of Muslim North Africa and West Africa. His ideas helped to rationalise French colonial rule. Al-Afghani and many other Muslim intellectuals wrote rebuttals of Renan’s arguments, while being supported by Blunt. But Renan enjoyed more success in creating a distracting narrative of a separate Islamic civilisation versus a Western, Christian civilisation.

European elites’ claims of a Western civilising mission, and the superiority of the Christian-Western civilisation, were important to the colonial projects. European intellectuals took up vast projects of classifying humanity into hierarchies of race and religion. It was only in response to this chauvinistic assertion that Muslim intellectuals fashioned a counter-narrative of Islamic civilisation. In an attempt to assert their dignity and equality, they emphasised the past glory, modernity and civility of ‘the Muslim world’. These Muslim opponents of European imperial ideology – of the white race’s civilisational superiority over Muslims and other coloured races – were the first Pan-Islamists.

During the early 20th century, Muslim reformers began to cultivate a historical narrative that emphasised a shared civilisation, with a golden age in Islamic science and art, and its subsequent decline. This idea of a holistic Muslim history was a novel creation fashioned directly in response to the idea of a Western civilisation and the geopolitical arguments of Western/white racial unity. Like the early generation of Pan-African and Pan-Asian intellectuals, Muslim intellectuals responded to European chauvinism and Western orientalism with their own glorious history and civilisation. Throughout the 20th century, the great Muslim leaders such as Turkey’s Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, Nasser in Egypt, Iran’s Mohammad Mosaddeq and Indonesia’s Sukarno were all secular nationalists, but all of them needed and used this notion of a glorious history of Muslim civilisation to talk back against ideologies of white supremacy. Nationalism eventually triumphed, and during the 1950s and ’60s the idea of Islam as a force in world affairs also faded from Western journalism and scholarship.

Pan-Islamic ideologies did not resurface again until the 1970s and ’80s, and then with a new character and tone. They returned as an expression of discontent with the contemporary world. After all, gone were the heady days of mid-20th-century optimism about modernisation. The United Nations had failed to solve existential issues. Post-colonial nation-states had not brought liberty and prosperity to most of the world’s Muslims. Meanwhile, Europe, the US and the Soviet Union showed little concern for the suffering of Muslim peoples. Islamist parties such as the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt and Jamaat-e-Islami in Pakistan appeared, maintaining that the colonisation of Palestine and the tribulations of poverty required a new form of solidarity.

Ideas of Western and Islamic worlds seem like enemies in the mirror

The Iranian Revolution of 1979 proved a historic moment. To condemn the status quo, Khomeini appealed to this new form of Pan-Islamism. Yet, his Iran and its regional rival Saudi Arabia both privileged the national interests of their states. So there has never been a viable federative vision of this new Pan-Islamic solidarity. Unlike Pan-Africanism, which idealised black-skinned populations living in solidarity within post-colonial Africa, Pan-Islamism rests on a sense of victimhood without a practical political project. It is less about real plans to establish a Muslim polity than about how to end the oppression and discrimination shared by an imagined global community.

The calls for global Muslim solidarity can never be understood by looking at religious texts or Muslim piety. It is developments in modern intellectual and geopolitical history that have generated and shaped Pan-Islamic views of history and the world. Perhaps their crucial feature is the idea of the West as a place with its own historical narrative and enduring political vision of global hegemony. The Soviet Union, the US, the EU – all the global Western projects of the 20th century imagine a superior West and its hegemony. Early Pan-Islamic intellectuals developed Muslim narratives of a historical global order as a strategy to combat imperial discourses about their inferiority, which suffused colonial metropoles, orientalist writings and European social sciences. There simply could not be a Pan-Islamic narrative of the global order without its counterpart, the Western narrative of the world, which is equally tendentious as history.

Ideas of Western and Islamic worlds seem like enemies in the mirror. We should not let the colonisers of the late-19th century set the terms of today’s discussion on human rights and good governance. As long as we accept this tendentious opposition between ‘the West’ and ‘the Muslim world’, we are still captives to colonisation and the failures of decolonisation. In simply recognising and rejecting these terms of discussion, we can be free to move forward, to think about one another and the world in more realistic and humane ways. Our challenge today is to find a new language of rights and norms that is not captive to the fallacies of Western civilisation or its African, Asian and Muslim alternatives. Human beings, irrespective of their colour and religion, share a single planet and a connected history, without civilisational borders. Any forward path to overcome current injustices and problems must rely on our connections and shared values, rather than civilisational tribalism.

[This article first published by AEON]