There was a time when economics was popularly known as political economics. One of the best political economists of the 19th century, Henry George, once said, “For the study of political economy, you need no special knowledge, no extensive library, no costly laboratory. You do not even need textbooks nor teachers, if you will but think for yourselves.” Unfortunately, this statement cost Mr George the chair of political economy at the University of California, where he had made it. But more unfortunately for us, ignoring his statement and not thinking for ourselves has led to the rise of today’s neoliberal economists who have all but tarnished this once noble profession.

But if we do take a few moments to think for ourselves, we can easily discern why economics was once called “political economics”. A great majority of geopolitical decisions have been, and continues to be, influenced by economics. By looking at it the other way, it can also be argued that economics has also been greatly affected and influenced by politics — political movements, decisions, changes, etc — and continues to be so. Overall, economics was called political economics because in the real world, the best way to analyse economics is by analysing the politics of the situation as well, because the two are often, if not always, correlated.

Growing trade deficit with India and China

Historically, trade between Bangladesh and India has been lopsided — dominated by Indian exports to Bangladesh, with Bangladeshi exports to India being significantly lower. In the 2014-2015 fiscal year, Bangladesh imported 6.5 billion dollars worth of goods from India and exported to India only 527 million dollars worth of items (“Bangladesh-India trade deficit swells manifolds in last decade”, bbarta24.net, March 29). According to economic analyst Mamun Rashid, “While India exports to Bangladesh more than 250 items, Bangladesh is exporting only six to seven items including jute, jute goods and readymade garments.” As such, “Bangladesh should look to diversify its exports there.”

The Bangladesh government now has a perfect opportunity to not only benefit its own people, but the people of the entire region. There is, however, no doubt that it will also need the cooperation of the other players in that regard.

China, which accounts for more trade than any other country in the world, is also Bangladesh’s largest source of import. But while Chinese products account for 29 per cent of all our imports, Bangladesh sends only 1.9 per cent of its total exports to China. In the first half of this financial year, Bangladesh’s trade gap with China increased by 18.44 per cent to $4.35 billion from $3.67 billion, despite a zero-tariff export facility for a number of Bangladeshi items to the Chinese market (“Trade gap with China rises to $4.35b in H1”, New Age, March 17). While Bangladesh imported $4.70 billion worth of goods and services from China, it managed to export only $349.78 million there. According to the Shanghai Daily, Bangladeshis are showing an increasing interest in Chinese products. “About 99 per cent of all Bangladeshis say they ultimately prefer a Chinese product whether for personal use or for commercial purposes, according to recent statistics… People here [Bangladesh] say that whatever it is they have to buy, they first look for a Chinese option because they are durable, on the one hand, and affordable, on the other” (“Bangladesh’s forward-thinking youngsters see China as path to bright future”, Shanghai Daily, March 7). No such trends have, unfortunately, been observed in China for Bangladeshi products.

Bangladesh’s major exports to China are garments, jute goods, knitwear, frozen food, raw jute, leather and agricultural products, according to the Dhaka Chamber of Commerce and Industry. Bangladesh, on the other hand, imports a much more diversified basket of goods and services from China. Many of them, however, are either raw materials or capital machineries that are used in the production process — products that cannot be easily, if at all, replaced in the short run and, in fact, are essential for economic activities and the overall economy. According to a Bangladesh Bank official, although “Bangladesh exported readymade garment products worth more than $13 billion to the global markets… the country’s export to China was very paltry considering the size of the market. So, the RMG sector should give attention to the issue.” While the RMG sector should, in order to increase its market share in China, follow the advice, the government should realise that part of the reason for Bangladesh’s poor export performance in China is because of its overdependence on garments export.

China itself is a massive producer of garments. And as the Chinese leadership has been constantly emphasising in recent times, it aims to increase its domestic consumption to reduce its overdependence on exports to maintain its current levels of production. This means that it will be increasingly difficult, especially for a nation such as Bangladesh which does not necessarily produce products of superior quality, to export goods that China already abundantly produces such as garments. Fortunately for Bangladesh, while its overdependence on the export of garments is a major reason for its poor export figures to China and to an extent to India, it also provides the perfect opportunity for Bangladesh to finally diversify its exports to other products. Such diversification will, however, require massive amounts of investment.

Investment opportunities

Luckily for Bangladesh, quite a few countries including China are keen to make such investments. In regards to the growing trade deficit that Bangladesh has with China, Chinese ambassador Ma Mingqiang said that “Only exporting to China would not help to reduce the deficit much… it would require huge Chinese investment here [Bangladesh]… China is keen to transfer advanced technology to support the efforts in Bangladesh, building economic zones and training the Bangladesh labour force to create more employment and strengthen the inner impetus for Bangladesh’s sustainable development” (“China keen to invest: envoy”, New Age, March 22). Furthermore, according to Mingqiang, by taking the right steps, “Bangladesh can emerge as a manufacturing hub.”

Two of the major types of investment that China and the other nations are interested in are in the power sector and in deep sea port development. Once again, they are both very favourable for Bangladesh and can be of massive benefit for developing its economy. For one, power is essential for the manufacturing sector and, indeed, for business and economic activities and the shortage of power has been a major drawback for businesses in the past. On March 30, Reuters reported, “Bangladesh-China Power Company Limited will invest $1.56 billion in a coal-fired plant near a proposed sea port south of Dhaka to produce 1,320 megawatts of electricity by 2019.” India is also keen to join the party. “The state-owned Indian electrical company, Bharat Heavy Electricals Limited, has recently signed a memorandum of understanding on a $1.6 Billion Power project at Khulna, Bangladesh” (“India–Bangladesh economic ties gain momentum”, East Asia Forum, March 18). And Malaysia too, as the Financial Express reported on March 14, “The government gave Sunday the go-ahead to a Malaysian company for setting up a coal-fired power plant with the generation capacity of 1320 megawatts on Maheshkhali island… ‘Not only Malaysia, another group from China is also negotiating for setting up another power plant also at Maheshkhali’, he [finance minister] said.” All of these suggest two things; first, many countries are showing interest in helping to develop the power sector in Bangladesh and, second, this has the potential for friendly and, perhaps, bitter rivalry between these countries to set in over gaining the rights to these development projects. Some indications of that rivalry have already been seen between China, India and Japan in the port development projects.

The question is whether after being victims of the divide and rule strategy and being played off against each other for so long, can we all finally think for ourselves and figure out that cooperation is our best way forward?

Enter geopolitics

The cancellation of the proposed Sonadia port is a clear example of the brewing rivalry, mainly between China and India backed by (or at the bidding of) the United States, that is actively seeking to “contain China’s influence” both globally and regionally. Economics professor Moinul Islam, a former chairperson of the Bangladesh Economist Association, at a recent regional seminar said, “Sonadia deep sea port will not be established in the near future due to geo-political reasons. India has reservation to allow China to come at the Bay of Bengal” (“Sonadia deep sea port’s future is bleak, says Economist Moinul Islam”, Bdnews24, March 20). Although the official reason provided by the Bangladesh government for the cancellation which, it has to be said, is stuck between a rock and a hard place, was a lack of commercial viability, the proposed Japan-developed Matarbari port is only 25 kilometres away. Thus, it is quite obvious that the real reason for the cancellation was geopolitics.

Even the planning minister has said that “the port deal would not proceed because ‘some countries, including India and the United States, are against the Chinese involvement’” (“Indian power deal with Bangladesh highlights geo-political rivalry”, World Socialist Web Site, March 5). Although, in this case, Bangladesh and China are both the victims of geopolitics, Bangladesh clearly is the bigger loser. China has already carried out extensive feasibility assessments and even agreed to provide 99 per cent of the necessary funds to build the port. Neither of these “objectors”, however, have provided an alternative as beneficial to Bangladesh as the one proposed by China. Of course, one must not forget that the proposed Sonadia project was also very beneficial for China also (to its “string of pearls” strategy). That is why China had proposed it in the first place.

But the economic loss for Bangladesh from such geopolitical pressure is enormous. Not only does it cost Bangladesh a much-needed deep sea-port, that too, mostly financed by China, but one must also consider the lost employment, trade connectivity and access to markets into that loss. The port could have easily given a massive boost to Bangladesh’s economy through increased export to all regions because of greater connectivity and through the lowering of transport costs. And it is pressure politics from India which is the main cause of such a loss. And what is most unfortunate in this case, is that, by playing the role of Washington’s puppet in trying to “contain China” by throwing obstacles in its way, India and other nations — which have for centuries been victims to the British invented, Washington-perfected “divide and rule” strategy — continues to fall victim to it, leading to losses for the entire region.

Can the Bangladesh conundrum be a boon?

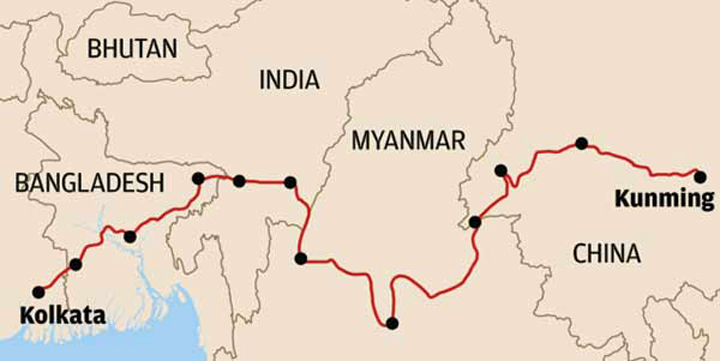

Despite India’s protests, the truth of the matter is that it is China that is doing the most to develop this region, in its own interest, of course, as it realises that its western partners are unwilling to see China rise any further. And the Belt and Road (Silk Road) initiative is a true testament to that fact. And if the governments of all the nations of this region truly think for themselves, they will see that its success will be of benefit to all. Bangladesh included. According to the top leadership of China, “China stands ready to work with Bangladesh to strengthen the synergy of bilateral development strategies through the Silk Road initiative and take their partnership to a new level” (“Silk Road initiative: China vows to take partnership with Bangladesh to new level”, Indian Express, March 26). And if India cannot see that one day its rise may be of concern to its western partners then that is most unfortunate.

This provides the Bangladesh government with a perfect opportunity to prove itself. If the government can strike a deal, through negotiations with the parties concerned regarding investment and development matters here, it may finally earn some respect both domestically and internationally for its diplomatic abilities.

Furthermore, if India does have concerns about China’s hegemonic ambitions and its growing influence, including in Bangladesh, then it should try to come to terms with China through dialogue — something its western partners, historically, are not known to do, except by using its superior muscle powers. That is exactly why both of these regional powers should see the benefit of mutual cooperation even more as it not only provides both with greater economic benefits but also with political ones. In that sense, cooperation on investing in Bangladesh would be a great start for everyone concerned and a good platform for building trust. As the Chinese ambassador has already said, “For the cooperation with other countries for [Payra] deep sea port we are open… if there is willingness to cooperate, we can do it together.” India should realise its own benefits from such cooperation and, thus, should have the “willingness to cooperate”. Otherwise, everyone loses out.

This provides the Bangladesh government with a perfect opportunity to prove itself. Historically, the incumbents and its predecessors have had a very poor track record of negotiating favourable terms for Bangladesh as diplomacy has never been the strong point of any government. If the Bangladesh government can strike a deal, through negotiations with the parties concerned regarding investment and development matters here, it may finally earn some respect both domestically and internationally for its diplomatic abilities. It can ignite the flame of better regional cooperation which may eventually lead to the solving of various other regional problems. Thus, the Bangladesh government now has a perfect opportunity to not only benefit its own people, but the people of the entire region. There is, however, no doubt that it will also need the cooperation of the other players in that regard. The question is whether after being victims of the divide and rule strategy and being played off against each other for so long, can we all finally think for ourselves and figure out that cooperation is our best way forward? That, remains to be seen.